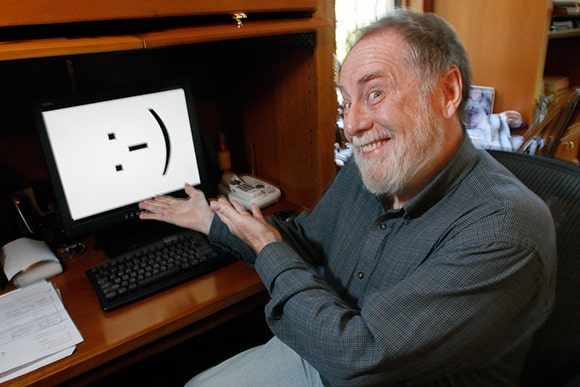

Scott Fahlman: The man behind the idea of Emoji

The Man Behind The Idea Of Emoji

Scott Fahlman: The man behind the idea of Emoji

You know, those emojis you use on a daily basis originally existed as emoticons. The first person to advocate using it in messages exchanged over computer networks was Scott Fahlman, a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. No one is precisely sure when the first one was used, though. Let’s get to know Scott and discover more about his cultural phenomes

The Internet was a very different place in the early 1980s than it is now. The World Wide Web was developed by computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee, who was built on the Internet’s development by dozens of visionary scientists, programmers, and engineers. However, before the internet, email was still in its infancy, and online discussion forums connecting academics, staff, and students (known as bboards) were growing in popularity.

The messages were sometimes misinterpreted because there weren’t the emoticons we use now to convey comedy or sarcasm.

Nobody knew for sure.

Scott Fahlman stepped into the picture at that point. Scott, a computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, accidentally invented the first emoticon, a sort of sideways happy face with two eyes and a nose, during a discussion on how to solve the problem. In order to convey his discontent, annoyance, or wrath, he also turned the smile upside down into a sad face.

It was September 19, 1982, that made history.

We had local email and had recently acquired the ability to send emails to a few other colleges over the outdated networks, according to Scott. But there wasn’t much to work with because it was just text and only the U.S. English alphabet.

The distinctive character sequences immediately gained popularity at Carnegie Mellon and spread to other universities and research facilities across the world via computer network message boards. Different “smileys” started to appear after a few months, and soon there were hundreds of them.

One of these was the astonished, open-mouthed smiling. Another was smiling with spectacles. Eventually, Scott’s original ideas came in noseless iterations.

The noseless models didn’t gain popularity until much later, in the 1990s, according to Scott. “I blame mobile phones for having poor keyboards since they forced users to type as little as possible, especially when it required non-alphabetic characters,” the author said.

Then, when folks with (obviously) too much time on their hands made emoticons that resembled Abraham Lincoln and Santa Claus, things got extremely imaginative.

Of course, there are many who contend that Scott didn’t invent these so-called emoticons until 1982. And Scott does not downplay the possibility. After all, he believes it to be a rather easy and clear concept.

They might have been utilized by teletype operators in the past. They might have been used in private correspondence well before the 1980s. There is no supporting data for such arguments, which is an issue. However, there is evidence to support Scott’s initial hypothesis.

He deleted the initial post where he suggested using an emoticon, mostly because he didn’t think it would make a major difference. But when the smiling face became a major phenomenon, he realized he needed to take the search seriously.

After several failed initial attempts, Scott’s friend Mike Jones, a CMU graduate who was employed by Microsoft at the time, organized and funded a kind of archaeological dig to locate the original message on the school’s old backup tapes, searching and deciphering antiquated media to finally unearth Scott’s smiley-faced suggestion.

What about the first emoticons?

They continue to be famous, but technology frequently intercepts them through word processing and content management systems, turning them into tiny graphics rather than the original character string. It “destroys the quirky character of the original,” in Scott’s opinion.

Nevertheless, he developed a tool that almost everyone can claim is now a part of their current day communication life, whether it be via emails, texts, or even handwritten letters. The emoticons developed into a distinct culture, inspiring animated adaptations and taking the place of written text.

How does he feel about being such an influence on society?

He acknowledged, “This was 10 minutes of my life, simply a foolish online chat more than 35 years ago. So, while it may be unusual to become well-known for something, it may be enjoyable to do so. No matter what I accomplish in my career as an AI researcher, I’ve come to terms with the fact that the first line of my obituary will include the development of the smiley face. I suppose that 10 minutes were well spent if I was able to avoid a few online misunderstandings along the way and if folks enjoyed themselves with these things.